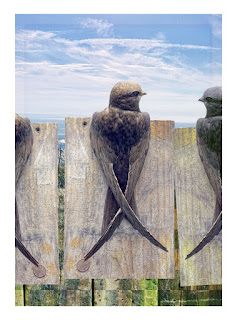

Swifts are extraordinary birds. Many of us wait anxiously for their return in early May each year as evidence that, despite their declining numbers, "the globe’s still working, the Creation’s / Still waking refreshed" (Ted Hughes, "Swifts"). Our swifts – "ours", as in the ones that choose to fly over our street, and presumably nest somewhere nearby – turned up on the 10th, five days earlier than last year, but a full fifteen days later than in 2020, which was exceptionally early (I keep a phenological notebook of such things). Welcome back, guys!

There is an article on dwindling swift populations in the current RSPB magazine – down an appalling 58% since 1995 – which includes this rapid-fire recital of swiftiana:

Everything except nesting is done on the wing: eating, drinking (scooping raindrops or making low passes over still, open water), mating, sleeping (dolphin-like in part torpor, up near Earth's stratosphere), and preening and bathing (cruising slowly through rain). When they arrive at their nest, it will usually be the first time they've touched anything solid in 10 months. In the case of young birds (which begin breeding at four years old) it could be three years or more.

Three years on the wing! It is estimated that in an average lifetime (5.5 years) a swift will have flown 4 million miles, sometimes at speeds nudging 70 m.p.h., and all fuelled by nothing more than airborne spiders and flying insects. There must be some dietary secret they're not telling us, although it would take a lot to persuade me to eat flies and spiders ("Southampton residents are going crazy for this one weird energy diet"). Besides, as I have never yet seen a dead swift, I suspect that they eventually simply explode from an excess of fizz somewhere up in the stratosphere.

That recital of swift Fun Facts reminded me of a track on an album I bought back in 1980; in fact, one of the very last vinyl LPs I ever did buy. The album was Miniatures, a compilation of fifty-one one-minute tracks assembled by Morgan Fisher (one of those influential but uncelebrated been everywhere, done everything, worked with everyone types), and the track was "A Swift One" by the drummer of The Pretenders, Martin Chambers. If you listen to the track – it'll only take a minute – you'll see why it came to mind.

It seems the Miniatures album had a follow-up in 2000, and they have attracted something of a cult following. Which is not surprising: it's exactly the sort of thing that would. I see Morgan Fisher has even been blogging about it in recent years. The list of participants is extraordinary: from R.D. Laing and Michael Nyman to Fred Frith and Robert Fripp, via Gavin Bryars and Ivor Cutler. If you have never heard of any of those luminaries, then you were clearly never the target audience for the album. That's what makes this a cult record, of course, along with the unifying concept, the DIY aesthetic, and the small-label limited distribution. It's a perfect piece of cultish, "underground", alternative art-making from the late 1970s. It's also utterly self-indulgent, and remarkably boring. I think I listened to it twice. I still have it, however, complete with its poster, as it seemed destined to become a "collector's piece" (my shelves are full of such white elephants waiting for their moment).

In retrospect, I think that album marks the point when I finally realised and came to accept the difference between what I thought I should like, and the things that I actually liked, which is a sort of maturity, I suppose. In 1980 I was 26, coming towards the end of my first contract of employment as a "graduate trainee" in Bristol University Library, and at that critical stage when one has finally to choose between, on the one hand, the vague hope that a hedonistic youth based on an "alternative" lifestyle might be an infinitely extendable condition and, on the other, taking a long, sober look down the rocky road ahead in order to make some decisions about life as an adult. I chose the latter, not without regrets, but in the process seemed to free myself from the sort of snobbish group-think that used to emanate from the pages of achingly hip, fashion-forward music weeklies like the NME. The fact was that at 26 I already felt too old for punk and its aggressively adolescent posturing (despite the fact that most punk acts were actually around my age), and I was ready to admit that I really didn't care if I never heard Trout Mask Replica, "free jazz", Miniatures, or any atonal music ever again in my life. Or, indeed, anything whose sole attraction was its rebarbative cleverness or difficulty, like a high fence topped with razor wire, surrounding nothing very much at all.

But something I liked then and still do, is to watch those high-flying, high-performance birds, the swifts, swallows, and martins. Just to stand and watch them. There's a meadow next to the Itchen Navigation canal near Winchester where you can stand on the waterside path and be buzzed at high speed by them as they flicker in low for a sip of water or to take mayflies. It's an amazing, mesmerising experience, and one that I enjoyed amplified to the max in 1981, on a narrow path halfway up the Cares Gorge in the Picos de Europa of Northern Spain, where an open aqueduct has been engineered into the rockface, and swallows zip in to dip their beaks within feet of your face, like a living museum diorama. If I had to think of a musical equivalent to what it might be like to be one of those birds, I suppose it would have to be "A Short Ride in a Fast Machine", by John Adams. Whoosh!

1 comment:

Enjoyed this piece Mike. We have House Martins here — I like to watch them in the summer evenings.

Post a Comment