I had some fun making this latest digital collage – if you read the previous post you'll know where it started – and the result is quite pleasing, I think, in a subtle kind of way. It reminded me of various posts I have written in the (so far) 15-year life of this blog concerning my lifelong fascination with moths, so I thought I'd extract the best bits from them, and revise and combine them here in another sort of collage. It's lazy, I know, but I doubt even long-term readers [insert variation on "both of them" joke here] would have noticed if I hadn't pointed it out. The fact is, however, that some of my better bits of writing are lurking in posts more than a decade old that nobody will have read since they were originally published, and my current inclination is to dust off and polish up any that come to mind.

So, some of my earliest memories are of driving home in the dark from our weekly Sunday visit to my maternal grandparents, who lived out in a village in rural North Hertfordshire. On late-summer nights on those country lanes we'd be assaulted by a constant barrage of moths strafing the car like tracer bullets. Occasionally, a huge one would be sucked into the mighty vortex of the propellers of our Austin A40 fighter-bomber, gleam for a brief moment as brightly as the cat's eye reflectors embedded in the centre of the road, and as quickly vanish into the surrounding total blackness. Sadly, it's an experience of abundance that is now as lost in the past as listening to Two-Way Family Favourites at Sunday lunchtime on the BBC Light Programme. Or indeed the transformative imagination of my eight-year-old mind.

The newly-built council house in which I spent the first half of my young life in Stevenage New Town was backed by a venerable copse (or "spring", in Hertfordshire dialect) which had been left more or less intact, and it, too, was still bursting with insect life. Emerging from the dark of night, the moths which settled on our kitchen window would tremble with some unknowable ecstasy, and seemed like envoys from another dimension. Let us in, please let us in! We have tidings of great strangeness to impart! Needless to say, we went to great lengths to keep them out.

If they did manage to get inside, though, that ecstasy would be unleashed as fury. There is something profoundly disturbing in the way a large moth will hurl itself around a room, in the same frenzy as a fish landed on a riverbank or a cat in a sack, knocking itself to pieces in the blindness of its contradictory desire both to immolate itself and to tear itself free from its spellbound condition. Eventually, exhausted and broken, the moth would vanish from sight, and the next day the smouldering wreckage would turn up under a chair or inside a shoe: message undelivered, mission impossible.

I became fascinated by these dead husks, that – looked at closely – resembled alien spacecraft made of intricately-engineered parts, decorated with a pagan, earthy camouflage that had a satisfying harmony of colour and shape. Some even had markings in a strange, organic alphabet like the lettering that came with the transfers ("decals") of a plastic assembly kit. A magnifying glass would only enhance the wonder. Your gently exhaled breath would cause the defunct antennae and landing gear to tremble, and the hairy thorax would ripple like a tiny meadow of sun-browned grass.

The next step after wonder, of course, is knowledge. I still own the copy of The Observer's Book of Larger Moths and the two-volume Moths of the British Isles I received as end-of-year prizes in primary school. I spent hours bent over these catalogues of entomological marvels, feasting on their taxonomies of similarity and difference served up on glossy coloured "plates", in much the same way my own children would later pore over Pokémon cards. The main difference being, of course, that moths are real.

Their wonderful names alone invoke enchanted Edwardian summer nights spent "sugaring", sweeping kite-shaped nets around in the dark, and finessing captive moths into cardboard pill-boxes: Angle Shades, Clifden Nonpareil, Burnished Brass, Brindled Beauty, Silver Y, Hebrew Character, Snout, Toadflax Brocade, Foxglove Pug, Pebble Prominent, Autumn Green Carpet, Lunar Marbled Brown, Jubilee Fan-Foot... On and on and on... There are many hundreds of native moth species in Britain with "common" names alone (and about 2,500 in all), compared to the mere 60 or so native butterflies. This hidden abundance and diversity is part of their mystery, and its depletion in recent decades is a little-noticed ecological catastrophe. I suppose that unless you have experienced for yourself a drive through that nocturnal blizzard, or seen a dozen or more moths of assorted shapes and sizes clinging to an urban windowpane, you will have no idea of the devastation that has been taking place.

Inevitably, collecting followed knowledge. This is something I regret now but – like birdnesting – back then it was regarded as a normal and instructive outdoors activity, and far better than slouching around all day with a comic; you could even earn a badge in the Cubs for it. Incredibly, a ten-year-old could walk into any High Street chemist shop, demand a half-crown bottle of ether or ammonia ("for my killing bottle, please, mister"), and leave with their deadly purchase in a paper bag, no questions asked.

Our neighbours would be mystified when we pegged a bed-sheet to the washing line on muggy summer nights, together with a high-wattage lightbulb on an extension cable. The nocturnal messengers would come thick and fast, drawn out of the copse and neighbouring gardens like children to the Pied Piper's ice-cream van bell. I won't go into the details of what happened next, as I have no desire to attract hate-mail. Suffice it to say that I had made my own killing jar, relaxing box, and setting boards out of household items and balsa wood, and achieved a pleasing level of skill in the business of miniature taxidermy. [1]

That was all a very long time ago, but I still get a little charge of excitement when I see the Humming-bird Hawk-moths working our buddleia bush on September evenings, or come across a Red Underwing sheltering in the eaves of the garden shed. And my family sounded the true depths of my moth-madness when, twenty summers ago, they found me crouching in a Brittany car-park at dusk, where twelve individuals of three species of very large hawk-moth – Privet, Convolvulus, and (I think) Striped Hawk – were feeding in a blur of wings on the municipal hydrangeas. Very nice, they said, but we're hungry, and left me squatting there, entranced, as they went to claim our reservation at the crêperie on the other side of the square.

Others feel the fascination, too, of course. Artist twins Doug and Mike Starn have produced some extraordinary photo-based images of moths, collected in their very desirable book Attracted to Light. Photographer Emmet Gowin, perhaps best known for his intimate family photographs of the 1970s and his aerial landscapes, has dedicated himself to a late-life project documenting the moths of Central and South America (his wife Edith, who features so prominently in the earlier work, is an entomologist). Two wonderful books – Mariposas Nocturnas: Edith in Panama and Mariposas Nocturnas: Moths of Central and South America, a Study in Beauty and Diversity (check out the video at that link) – have been the result. In Britain, printmaker Sarah Gillespie produces spectacular large mezzotint images of moths, also collected in a beautifully-produced book, Moth. No doubt there must be others, too, who are susceptible to their magic.

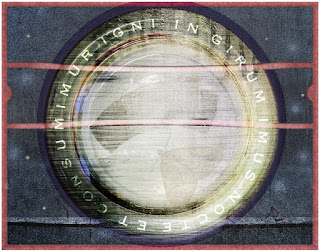

A while ago I came across Situationist Guy Debord's last film, made in 1978, called In Girum Imus Nocte et Consumimur Igni. That bizarre title, I discovered, is both a Latin palindrome and a riddle, which translates roughly as "We go around in the night and are consumed by fire" (spoiler: the official answer is "moths", not "Catherine wheels" or "drunks at a Bonfire Night party"). It's well known, apparently, but something I'd certainly never come across before (a large category, admittedly). Once you start digging on the Web, it quickly emerges as a popular text within certain demographics, including makers of indie music and bearers of pretentious tattoos, most of whom couldn't tell an ablative from their elbow. So, well, why not? As a sometime moth-botherer with a little Latin I might as well make use of it, too.

1. Despite giving up the hobby in my teens, I kept my boxed collection of moths – I suppose as a reminder of a path not taken – and it followed me loyally over the years. However, I hadn't actually opened it for decades until one day in 2016. Yikes. Over fifty years most of the contents had been reduced to dust, leaving just ranks of pins and paper labels standing among scattered limbs and fragments of wing. What I'd been keeping was not so much a collection as an insect charnel house. It was clearly beyond saving, so I simply vacuumed the lot out, taking on board the Great Teaching I'd just been handed about holding on to things for too long, courtesy of the unsentimental forces of entropy. Though it was still with some regret that I chucked the box into the "mixed timbers" skip at the Recycling Centre the next day.

3 comments:

My schoolboy sins were more about oology than lepidoptery, but I've had two occasions this summer when I had to find out more about moths. The first was when my wife moved a display cabinet to clean behind it and discovered what turned out to be egg cases of a carpet moth - not a happy encounter. But then a few weeks later I looked out of the kitchen window and was very confused to see what looked like a hummingbird feeding on our jasmine bush. I'd never seen or heard of these beautiful hawkmoths before - it cheered me up for the rest of the day.

old_bloke,

Yes, "moths" in most people's reckoning are what fly out of a miser's wallet... We have an eternal struggle with clothes moths here. But aren't Humming-bird hawk-moths great? You might also see Bee-hawks, too -- similar, but smaller. Sadly, we haven't had any this year (they migrate over from Europe in late summer), they've probably all got heat exhaustion... It's heartening to hear you've had at least one.

Mike

What a great video with beautiful moths. Thank you !

Post a Comment