But no; at most, the work of many name-check philosophers and poets survives only as fragments or even just as quotations and references in the work of other, later writers. To the extent that the existence of some is little more than a rumour of a reputation, pieced together by scholars from hints and "Chinese whispers".

As it happens, one such scholar was my partner's grandfather, a tutor at Oxford named Cyril Bailey. In the first half of the 20th century he edited and wrote about Epicurus and his later Roman admirer Lucretius, author of De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things). I have already described how, at Christmas 2009, his pristine copy of the Aldine edition of Lucretius (published in 1515, more than a century before the first Folio!) turned up in a box of books inherited from one of her aunts (see the post Nice One, Cyril). Needless to say, this tenuous family-in-law connection has never prompted me actually to read that particular magnum opus, but it has sensitised me to passing mentions of the names Epicurus and Lucretius, much as my eye is caught by any mention of Letchworth in the news or in print, Letchworth being my father's home town, but a place in which I have otherwise no real interest at all.

From the little I have gathered about his philosophy, it seems that most of the more sensible people I have known have been instinctive Epicureans. With the hindsight of two and a half thousand years, it does seem pretty much like the application of common sense to the goal of achieving a happy, balanced life, like one of those life-hack listicles: moderation in all things, don't live in fear of what comes after death because there will be nothing, and so on. Recently, I came across an aspect of the Epicurean philosophy I hadn't encountered before, summed up in the phrase “live in obscurity" or "live unnoticed" (in Greek, λάθε βιώσας, lathe biōsas). Inevitably, there is debate about what exactly this might mean, but the gist seems to be that one should shun the political and public life, as to attract the attention of the authorities or the public was (and still is) a dangerous thing, and not conducive to the pursuit of the ultimate Epicurean goal, that happy, balanced life, one characterised by ataraxia (freedom from fear) and aponia (the absence of pain). Expressed in a more demotic idiom: keep your head down, never volunteer, and mind your own business, and you'll spare yourself a world of grief.

So-called "lazy girl jobs" and the post-Covid phenomenon of "quiet quitting" have been much discussed in recent times, and these seem like exemplary Epicurean strategies to me. That is, on the one hand to choose an undemanding but reasonably-paid job that leaves plenty of time and energy left over for friends, hobbies, or whatever, and on the other to give your job rather less than 100% of your time and energy, on the basis that some wage-slave occupation should not define or provide the meaning of your life.

Well, you'll get no argument from me on that score, you quiet-quitting, lazy-girl, present-day Epicurean slackers. As a lifelong exponent of the subtle art of remunerative and rewarding under-achievement (see the post Fail Better), I know something about keeping my head down, never volunteering, and minding my own business. You may suspect me of humble-bragging here – true, I did have a moderately successful and contented professional career, followed in retirement by a rather less successful stab at becoming an artist – but the rich, the powerful, and the ambitious have never had anything to fear from me. I was a librarian, FFS.

Yes, you say, but what about the heroes and Shakespearos? I'm reminded of the words of John Keats regarding would-be poets, which could be applied to life in general: "... it is easier to think what poetry should be, than to write it - And this leads me to another axiom - That if poetry comes not as naturally as the leaves to a tree, it had better not come at all". In other words, sure, give your best shot to whatever fantasy-life turns you on but, if at first you don't succeed, get a proper job. Ideally one with a decent pension attached, although these are scarcer, these days, I realise. After all, there are still plenty of useful things to do that will pay your bills without requiring you to sweat blood, lose sleep, give 110%, stay late in the office, or ultimately to suffer the slings and arrows of unfulfilled ambition. Have the courage to be ordinary.

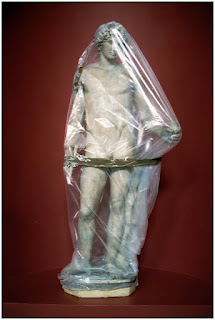

Epicurus aside, this is an acceptance of reality that commends itself to common sense, if not to ambition, not least when you consider the likelihood of some scholar piecing together anyone's "life and works" from whatever fragments are likely to remain after the depredations of another two and a half thousand years. By then, even Shakespeare may be little more than a rumour of a reputation, pieced together from hints and "Chinese whispers", along with that irretrievable 85% of the dramatic efforts of his contemporaries.

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air:

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp'd towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.

The Tempest, Act 4 Scene 1

Which would be – will be – a terrible shame, won't it? But I imagine very few, in those far-off future days, will have the inclination or the language skills to make sense of even a magnificent fragment like that, written in an obscure, high-flown dialect of a dead language. So we'd better enjoy it while we can and while we still have the whole thing, luckily for us, thanks to the First Folio, four hundred years old this year.