I recently bumped into a fellow pensioner in the supermarket, someone whose line-manager I used to be, and we had a pleasant catch-up chat about this and that while blocking the aisle with our trolleys, as is the right of all pensioners. It was enjoyable, and made me realise quite how much I miss the everyday human interactions of the workplace, despite not missing the workplace itself at all.

But it also prompted the thought that, unless you are by nature extroverted and gregarious, or perhaps just single and child-free, you will most likely have stopped making new friends in mid-life. Sure, there are the people whose company you enjoy at work, and there are the parents of your children's friends, as well as the odd congenial neighbour – let's not even think about social media "friends" – but these are not and will never be friends like the friends of your childhood and youth. You won't ever share a first cigarette or heartbreak at midnight in the park with these people, you'll never listen to their music or their secrets in their bedroom, and you will never have so much in common with them that you are all in effect just different avatars of whatever circumstances and influences you grew up with or grew into. You don't choose those friends any more than you choose your parents: they are a given of your most formative years. As I have said before, they are your elective family.

In an idle minute some while ago – there must have been a reason, but I can't now remember what it was – I started to make a list of the names of everyone I could recall whom I would, at some point in my life, have counted as a friend. It took a while – surnames can be annoyingly elusive – but in the end there were about 80 solid names in the list. Like most state-educated kids, I imagine, a few friends have been a constant from primary or secondary school right up to the present day, but I was surprised to discover that I am still at least "sort of" in touch with over a quarter of the listed names. I have no idea whether that is typical or not.

At least a further eight have died that I know of, but most of the rest are probably still out there somewhere, and revisiting the list put me into a sufficiently nostalgic mood to think of posting it here, as a sort of message in a bottle, floating on the internet. Who knew? Maybe the next time one of them googled their own name, or that of a mutual friend, they'd find this post and get in touch. What harm could it do? But then I realised: there are some very good reasons why I'm still in touch with some people, and not others. For a start, you don't necessarily like the people you once counted as friends, nor they you. You didn't really choose each other: you were simply there when it counted. The fact is that it was more the custom casually to lose contact in those pre-internet days than it was to stay in touch. A simple change of address would do it, and I myself had something like fifteen addresses between the ages of 20 and 30, which is probably fairly typical. Besides, the harsh truth is that fifty sometime friends had presumably never felt the need to get back in touch with me, either. I'm not difficult to find, after all.

That said, it can take a fair amount of searching skill to triangulate the right person on the internet. A name that is unique in one setting can be extremely common in another, and the internet has a way of obliterating all meaningful context; you're not so much looking for a needle in a haystack (and what a curious expression that is), as a needle in a haystack of needles. Take my own name, for example: it seems there are dozens of men called "Mike Chisholm" out there, especially in Canada, some of whom are also photographers, or artists, or librarians, or bloggers; although I'd hope no-one would confuse me with the bagpipers, politicians, and ice-hockey players. Scrutinising the sort of passport-quality photos that turn up online doesn't help much, either: it's very easy to convince yourself that some ageing, balding, jowly visage is a possible mutation of the fresh-faced young person you once knew, even though it usually isn't. The opposite can be true, too: I have at least three times stood face to face with old friends or work colleagues and not recognised them for who they were (OTOH I concede that I must start wearing my glasses).

In the end, all forms of nostalgia are a hunger that cannot be satisfied, a nagging pain that can never be assuaged, which is why it's best to avoid them. Someone else now lives in your childhood home, the fields you played in have been built over, and your old friends are as old as you and as irreversibly changed by their lives as you have been by yours. The chances that you still have anything in common are small. Probably the only real remedy is to have done the hard work of staying in touch, and to have gone through life's changes in parallel; otherwise your elective family, like those blood cousins you never see now except at family funerals, will become at best polite strangers, with rather less to say than the ex-colleagues you occasionally bump into in the supermarket.

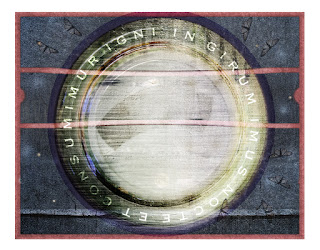

The most surprising people can be afflicted by nostalgia, though. How about this curious extract I came across this week, from Situationist Guy Debord's last film, made in 1978, called In Girum Imus Nocte et Consumimur Igni? That bizarre title, incidentally, is both a Latin palindrome and a riddle, which translates roughly as "We go round and round in the night and are consumed by fire" (spoiler: the official answer is "moths", not "drunks at a bonfire party"). It's well known, apparently, but something I'd never heard of before (a large category, admittedly); once you start digging into that haystack of needles, it quickly emerges as an extremely popular text within a certain demographic, including makers of indie music and bearers of pretentious tattoos. Hmm, Situationists, moths, night, circles... OK, I admit I could be in there, too, now, somewhere.

2 comments:

Mike, that is an outstanding photo. Beautiful, amusing, and good context for the post.

Huw

Thanks, Huw! Those are the moments photography is made for... Unfortunately, they don't come along that often.

Mike

Post a Comment