As anticipated in my post Sea City, Southampton failed to become City of Culture 2025 – no real surprise there, but come on, Team Soton, let's hear three muted and sarcastic cheers for Bradford! – and, more significant from where I stand, I failed to get either of my entries into the linked exhibition at the City Art Gallery. I'm not sure what difference this failure will make to the city, but I suppose you could say that at least my soul is getting the benefit of a decent work-out from the humility-inducing, hubris-squashing effects of serial rejection. Mmm, feel the burn!

There's a certain perception out there that, where the arts are concerned, rejection is a sort of back-handed compliment, something that will be rectified by posterity. Van Gogh didn't sell a single picture! People thought Blake was just a weirdo! Which rectification, in a very few exemplary cases, has indeed turned out to be forthcoming. But most failed artists and writers sink without trace, and with good reason: they weren't very good. Or, to put it another way, society had no use for what they made then, has so far found no use for it in the present day, and probably never will. Their labours have pleased no-one whose opinion counted then or counts now and thus, more grandly, will have added nothing to the story of art history. That is, unless a day comes when – as is happening now – some incidental feature of the artist's biography, say, such as their gender, race, or sexual orientation, bathes old work in a flattering new light. And, let's be honest, some pretty crappy new work is getting the spotlight right now, for precisely the same reasons.

So much depends on the tastes and motivations of those intermediaries such as the editors, the gallerists, and the judges of competitions – generally referred to as "gatekeepers" – and the narratives they want to impose on or derive from the raw material that hopefuls lay before them. It can be gratifying and amusing for us to see how dramatically the judgments of such gatekeepers have in the past failed to conform with the account we have subsequently come to accept as the "true" story. But this amusement is often no more than the superficial condescension of hindsight. I was reading a fascinating article in the New Yorker ("Modern Art and the Esteem Machine", by Louis Menand) which provoked the humbling thought that we, too, would most likely have scorned Matisse – Matisse! – as did sophisticated Americans in 1913:

The general American public, in the period when modern art emerged, around the time of the First World War, had no interest in it. Wealthy Americans, the sort of people who could afford to buy art for their homes, had no taste for it. Even the art establishment was hostile. In 1913, a Matisse show at the Art Institute of Chicago instigated a near-riot. Copies of three Matisse paintings were burned and there was a mock trial, in which Matisse was convicted of, among other things, artistic murder. The demonstrators were art students.In another recent article, this time on literary rejection ("Good God, I Can't Publish This...", by Rosemary Jenkinson), I see that a publisher's reviewer of the manuscript of Virginia Woolf's To the Lighthouse refused it, commenting,

"Self-publication may be your best hope. If your own milieu is anything like that of your novel, I trust you will have little trouble making connections or garnering finances..."

Even accepting that Woolf's book is now an established masterpiece of Modernism, I think we can still see what he was getting at, and feel a certain sympathy. The innermost musings of the idle rich and the cultivated classes? With not a single murder or cab-chase? Next manuscript, please... Plus, the fact is that he was right! The Hogarth Press was indeed a very successful self-publishing imprint set up and run by Leonard and Virginia Woolf.

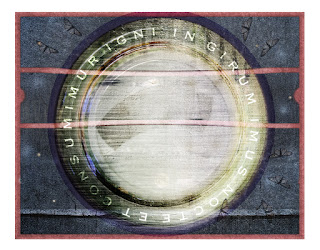

Anyway, FYI, FWIW, I've attached my own rejected efforts below. The brief for the exhibition was "What culture means to me" [1] and I adapted some existing work to meet the brief in what I thought was an interesting way. The framing texts are important, and in case you can't read them in the image I'll quote them here.

"Cultural Capital" has a (slightly adapted) extract from Marx's Economic & Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844:

"The less you eat, and drink, the fewer books you buy, the less often you go to the theatre, the dance-hall, the pub, the less you think, love, theorize, sing, paint, etc., the more you will save, and the greater grows your treasure which neither moths can devour nor thieves take away: your capital. The less you are, the less you express your own life, so the more you have; the more of your life you give up, the more you store up ... Well, what exactly?"

"My mind seems to have become a kind of machine for grinding general laws out of large collections of facts, but why this should have caused the atrophy of that part of the brain alone, on which the higher tastes depend, I cannot conceive. A man with a mind more highly organised or better constituted than mine, would not, I suppose, have thus suffered; and if I had to live my life again, I would have made a rule to read some poetry and listen to some music at least once every week."